Introduction 1983

Don't lose hope!

The second pilgrimage of John Paul II to his homeland had a significant impact on the Polish social and political reality, especially in terms of resistance to the communist dictatorship and pouring hope for a better tomorrow in the hearts of Poles. The Holy Father was initially to come to Poland in 1982. Due to the imposition of Martial Law and the protracted negotiations by the authorities regarding the conditions of the Pope's arrival, the visit was postponed to the following year. The talks about the pilgrimage were resumed in the autumn of 1982. The meeting of Archbishop Józef Glemp and Wojciech Jaruzelski on 8 November 1982 was of key importance for agreeing the positions of both parties. At that time, the initial date of John Paul II's arrival to his homeland (later changed by two days) and the most important conditions of the visit were agreed upon, being the subject of further intensive talks in the Joint Commission of representatives of the Government of the Polish People's Republic and the Polish Episcopate. During the meetings of this body - which, due to the stance of the party, turned out to be a painstaking process - the places which the Holy Father would visit were determined.

The authorities used every excuse to remove more cities from the program. In this way, Szczecin, Piekary Śląskie, Olsztyn, Łódź and Lublin were not on the pilgrimage route. Party dignitaries also contested particular points of the visit, e.g. in April 1983, at the Joint Commission forum, the Church suggested that during his stay in Poznań, John Paul II should visit the monument to the Victims of June 1956. In response, the head of the Office for Religious Affairs Adam Łopatka stated: "We will leave the stop at the Poznań crosses for the visit of John XXIV or John Paul V in a hundred years". The authorities tried in various ways to limit the attendance during the ceremony ̶ the need to ensure the Pope's safety served as a convenient excuse. The final pilgrimage program was set on 18 April and included Warsaw (16̶18 June), Niepokalanów (18 June), Częstochowa, Jasna Góra (18̶19 June), Poznan, Katowice, Jasna Góra (20 June), Wroclaw, Góra św. Anny (21 June) and Cracow (22̶23 June).

The bone of contention in the negotiations was the meeting of John Paul II with Lech Wałęsa. On several occasions, Wojciech Jaruzelski tried to convince Archbishop Glemp to persuade the leader of "Solidarity" to resign from a conversation with the Pope. Pressure in this matter was also exerted on Church negotiators. While the Primate basically agreed to the authorities' request, neither the Holy Father nor most bishops were willing to comply with the "wishes" of the party representatives. As stated by Cardinal Franciszek Macharski: "Let us not discuss whether we should suggest this to the Holy Father or not. If the Holy Father did not agree to meet him, he himself would loose his credibility." For this reason, the Pope's meeting with the leader of "Solidarity" took place, and it was of great importance for the opposition.

The Church and the faithful were carefully preparing for the pilgrimage, both spiritually and in terms of its organization and logistics. Special diocesan teams to supervise the organization of the visit and the order service of Totus Tuus (already known from the pilgrimage of 1979) were established. This was to control the pilgrimage route and ensure the smooth conduct of particular ceremonies.

During the preparations for the visit, the authorities of the Polish People's Republic had two main and complementary goals: 1) to thoroughly learn the plans of the hierarchical Church, clergy and opposition, and asses national attitudes; 2) counteract any events regarded as undesirable. The security apparatus defined the main goals of the undertaken actions as follows: "Counteracting, neutralizing and eliminating initiatives and activities of the anti-socialist opposition aimed at using the Pope's visit for politically hostile purposes". The pilgrimage was a time of unique mobilization and intensification of both the surveillance of Poles and operational activities by the Security Services.

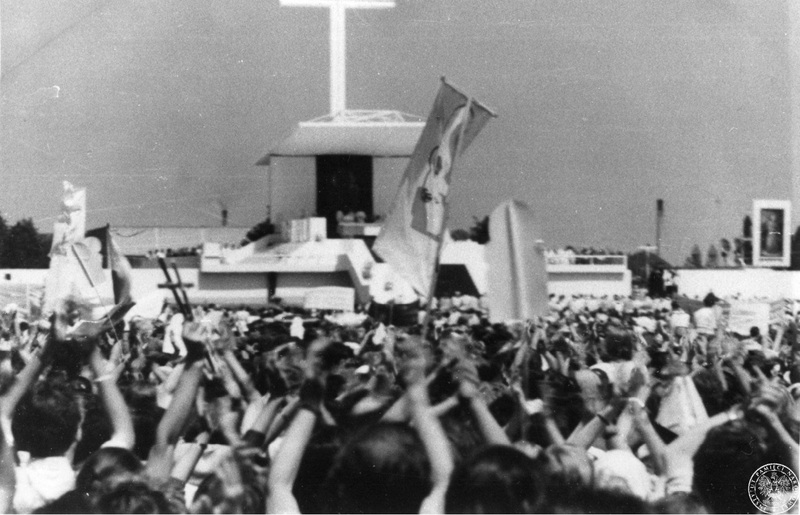

The second visit of John Paul II to his homeland began on 16 June with a greeting ceremony at Okęcie airport. The Holy Father came to Poland with the slogan: "Peace be with you, Poland! My homeland! " In his first speech he noted that he had come to all Poles. And so, it was. In every place of his stay the Pope was enthusiastically received by countless crowds. About 7 million Poles took part in the meetings with John Paul II, the largest number in Cracow at the Błonia greenfield - almost 2.5 million people. The mood was sublime and solemn everywhere, and the services were held in a peaceful and religious atmosphere, interrupted primarily by applause for the Holy Father.

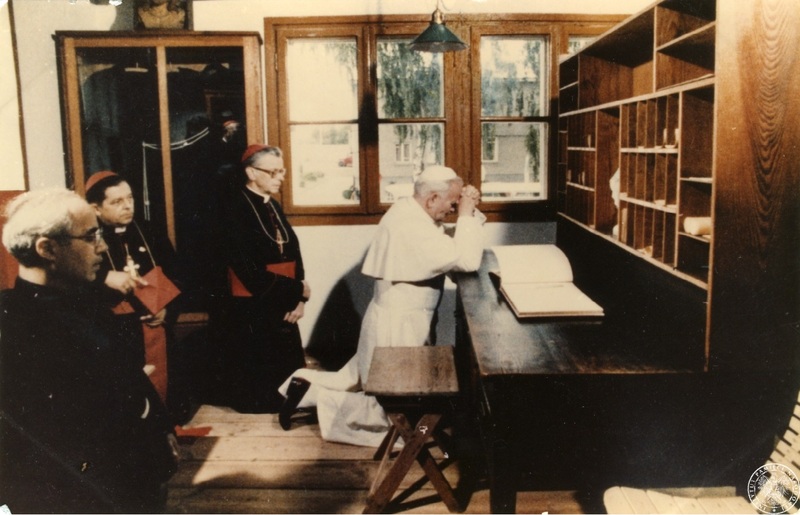

The authorities' propaganda concepts were already thwarted by the Pope in his homily, on the first day in the Warsaw cathedral: "Together with all my countrymen, especially those who most painfully feel the taste of disappointment, humiliation, suffering, deprivation of liberty, harm, trampled human dignity, I stand under the cross." The Holy Father’s subsequent speeches were received negatively by the communists, because he directed them to the terrorized society, and they were not subject to any governmental control. The words of John Paul II included clear references to "Solidarity" as a social movement, as well as to the universal brotherhood in suffering. They were in line with the Pope's stance on the freedom of the nation, collectivity and individually for each person. As we already know, government representatives ultimately failed todiscourage the Holy Father from meeting Lech Wałęsa on 23 June in the Chochołowska Valley. This was a clear testimony of the Pope's attachment to the trade union banned by the authorities.

During the visit, party dignitaries protested several times and threatened to amend its program. On the morning of 19 June, Adam Łopatka intervened with Cardinal Macharski and Archbishop Bronisław Dąbrowski. He emphasized that the government was indignant and bitter after hearing the speeches that John Paul II gave to young people and the one in Częstochowa: "We treat the content of homilies to young people as a call to rebellion and religious war. Does the Church want a row and a religious war in Poland? On 13 December 1981, the authorities proved that they were able to successfully oppose any attempts to destabilize the system and the state. The government reserves the right to adjust the visit program." The episcopate strongly rejected the accusations. In a letter signed by Archbishop Dąbrowski, he noted that the tone of the mentioned speeches did not differ from previous homilies, and then concluded: "Such sharp reactions of state authorities interfere with the dignified and calm course of the Second Pilgrimage of the Holy Father John Paul II to his homeland".

The Pope did not care about communist accusations and in the following days openly supported the freedom aspirations of Poles. He addressed representatives of the authorities with similar words. He met them five times during the pilgrimage. The most important of them took place on 17 June in the seat of the Polish government with the participation of Wojciech Jaruzelski. John Paul II strongly emphasized that Poles were one of the European nations, and said: "Despite the fact that life in the homeland has been subjected to the severe rigor of Martial Law, as it was suspended at the beginning of this year, I am still hopeful that this announced social renewal, according to the principles worked out in such an effort in the breakthrough days of August 1980 and contained in agreements, will gradually happen". The last part of the pilgrimage was the previously unplanned meeting of John Paul II and Jaruzelski at Wawel Castle on 23 June (on the day the Pope returned to the Vatican). It was organized at the request of the Holy Father. Unfortunately, we do not know the course of this conversation. Various residual information shows, however, that it was turbulent, and John Paul II called on the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party to stop repression and begin talks with “Solidarity” leaders.

In the opinion of most Poles, the Papal pilgrimage was a great success not only for the Church, but also for the entire nation. The Cracow secret police stated: "In religious circles there is a belief that the visit of the Pope has been a great success, especially for the Church. Its religious effects are unquestionable. According to the clergy, the huge interest and attendance of Christians at Papal ceremonies confirms the high level of religiousness of the Polish society, which made the authorities aware of the Church's strength as a possible partner for dialog.". In turn, George Weigel noticed that the Papal visit strengthened "the resistance of the Church and showed that there would be no agreement over »Solidarity«".

In the episcopate’s statement of 25 August - summarizing the effects of the visit of John Paul II – it was emphasized that: “The Papal teaching inspired all Poles with a new hope for a better future ... . The principle of dialog proclaimed by the Church must become a successful basis for internal peace and cooperation between Poland and the people of Europe and the world. When the dialog between the government and the nation ceases to exist, social peace is threatened and even disappears altogether." The authorities considered the words a far-reaching warning against them and used this as a handy pretext to aggravate actions aimed at the Church.

The visit of John Paul II to Poland in 1983 brought about significant results. On the one hand, the pastoral message of John Paul II and his teachings strengthened the Polish community. The position and authority of the Church also increased, and the society's hope for a better tomorrow was confirmed. On the other hand, the pilgrimage exacerbated the anti-Church activities of the communist authorities, who were concerned with the "wildness of the clergy", to quote Mirosław Milewski, Minister of the Interior.

Rafał Łatka, Ph.D.